Once the deal was done, the sisters were again made to walk for several days through the desert, this time north to the Mohave village, near the not-yet-founded city of Needles, California, and unsure of their fates all the while. The Yavapais ended up swapping them for some horses, blankets, vegetables, and an assortment of trinkets. The girls lived as the Yavapais’ servants for approximately a year, until some members of the Mohave tribe, with whom the group traded, stopped by one day and expressed interest in the Oatmans. The girls, Olive later said, were sure they’d be killed. The tribe’s children would burn them with smoldering sticks while they worked, and they were beaten often. Once they reached the Yavapai village, the girls were treated as slaves, made to forage for food and firewood. When they asked for water or rest, they were poked with lances and forced to keep walking.

Tied with ropes, the girls had been made to walk for several days through the desert, which triggered serious dehydration and weakened them in general. The Yavapais had taken the sisters, very much alive, to their village about 60 miles away, along with selected prizes from the Oatmans’ wagon. Marine 69-71, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 4.0, Because the volcanic soil was rocky and difficult to dig, it was not possible to bury the Oatmans, so cairns were built around their bodies instead.Ī marker at the site of where the Oatman family was attacked in 1851 in Dateland, Arizona. Badly injured, Lorenzo walked to a settlement and had his wounds treated, then rejoined the group of other Mormon emigrants, who returned with the teenager to the scene of the crime. When Lorenzo came to, he found six bodies, not eight: Two of his sisters, 14-year-old Olive and 7-year-old Mary Ann, were nowhere to be seen. Apparently, all of the Oatmans were murdered-all except Lorenzo, age 15, who was beaten unconscious and left for dead. The details of what happened next aren’t known, but the encounter somehow turned into an attack. Sure enough, about 90 miles east of Yuma, on the banks of the Gila River, the family was waylaid by a group of Native Americans, likely Yavapais, who asked them for food and tobacco. And that’s how Royce, his wife Mary, and their seven children, aged 1 to 17, found themselves trekking through the most arid part of the Sonoran Desert on their own. The other families elected to stay in Maricopa Wells until they had recuperated enough to make the journey, but Royce Oatman chose to press on. To continue, it was made clear, was to risk one’s life. When the remaining dregs of the Oatman-led party approached Maricopa Wells, in modern-day Maricopa County, Arizona, they were warned not only that the southwestern trail ahead was barren and dangerous, but that the native tribes in the region were famously violent toward whites. The group of approximately 90 followers had left Independence, Missouri, in the summer of 1850, but when they arrived in the New Mexico Territory, the party split, with Brewster’s faction taking the route to Santa Fe and then south to Socorro, and Royce (sometimes spelled Roys) Oatman leading a group to Socorro and then over to Tucson.

Brewster-they’d been advised that California was, in fact, the true “intended gathering place” for Mormons, rather than Utah. As newly inducted Brewsterites-followers of Mormon rebel James C. In 1851, the Oatman family, having broken from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was traveling through southeastern California and western Arizona, looking for a place to settle.

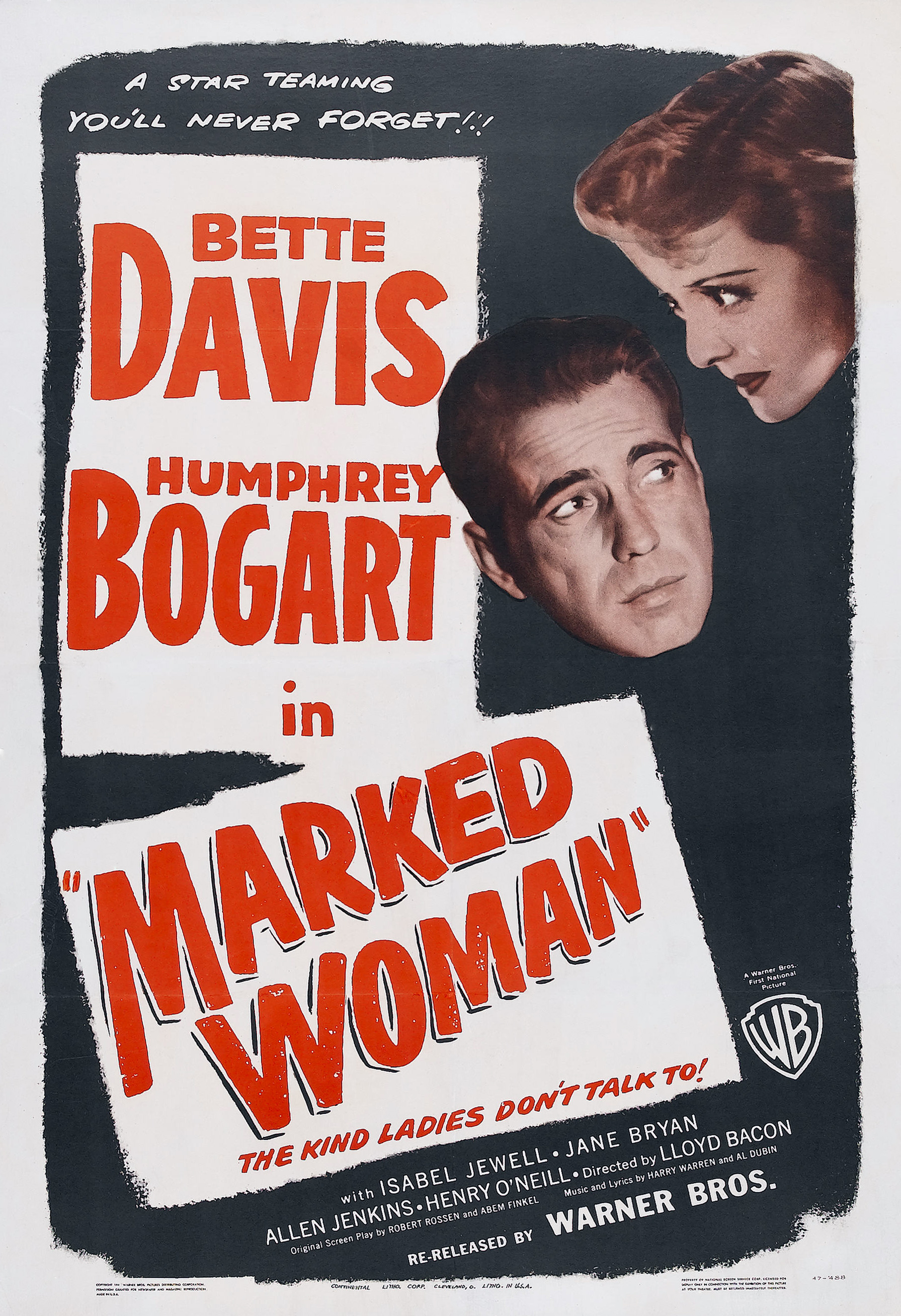

#Marked woman series

Through a series of strange tragedies (and some possible triumphs), a white Mormon teenager who was traveling with her family through the area in the mid-19 th century ended up sporting one too, a symbol of a complicated dual life she could never quite shake. About a century and a half ago, some Native American tribes of the Southwest used facial tattoos as spiritual rites of passage.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)